Much has been said and editorialized about Weston as a father – much of it less than complimentary. How else do you treat a man who abandoned his wife and children for an exciting jaunt to Mexico with a charming and alluring Italian-American movie starlet? What kind of father would do such an unspeakable injustice to his four young boys?

The reality of the situation is that Weston was a caring, loving, and nurturing father. His record had been tainted by his departure to Mexico and, even earlier, by his affairs while he maintained his Glendale studio. There, his young (they were born between 1911 and 1919) and impressionable sons were clearly influenced by circumstances that they could not fully understand. And, no doubt, their mother answered questions they may have had with a decided bias. Flora was, by many accounts, a domineering and overbearing individual who did not hesitate to use appropriate dosages if propaganda and misinformation to manipulate a situation. Edward suffered these influences for more than a decade under the same roof with Flora and subsequently for another decade beyond. It was not until his marriage to Charis Wilson that there appeared to be a relaxed approach. Distances of time and miles may be partly responsible for this change, as well as the maturing to manhood for each of their four sons. Yet, it may have been the strength of Edward’s relationship with Charis that forced Flora to relinquish her domineering position over Edward and his life.

Little is written or known of Weston’s children’s earliest years while he maintained his portrait studio in Glendale. Yet, the portraits of Chandler, Neil, Brett, and Cole taken during the years before 1923 and his departure for Mexico provide a portal through time that paints a portrait of Edward Weston the father as warm, loving, nurturing, and affectionate. Flora’s scrapbooks burst with countless images of these towheaded boys, who provide their father with the trusting and loving smiles of youth, comfortable in their surroundings and in the presence of their adoring photographer father. During these years, when Weston was still under the influence of Pictorialism, his sons not only smiled for his candid shots of them, but also served as models for some of his more passionate and moving works. It is clear that the father-son bond was strong from the very beginning. While on his first trip to New York City in 1922, Weston felt the pangs of separation from his sons. Seeing a friendly boy, his urge was to “crush him to me – thinking of my own lovely boys,” but he hesitated to do so for fear of being misunderstood. Despite his move towards greater personal independence in the early 1920s, Weston remained a dedicated father, and his sons returned his devotion and attention many times over.

It is hard to imaging how difficult it must have been for Edward Weston to leave three of his four sons for his journey to Mexico. Like many relationships, Edward’s and Flora’s became distant and contentious. Weston’s embrace of middle-class values and aspirations waned as the decade of the 1910s came to a close. For these, he substituted a mantra of experimentation, growth, and change, both in his personal life and with his work. His struggles were severe. On one hand, Weston was confronted by a marriage and home environment that had become unbearable to him. On the other were his yearnings for greater freedom and happiness. As was always the case with Weston, these yearnings were equally strong where his art and life were concerned. For Weston, they were virtually inseparable and indistinguishable from one another.

Weston was only thirty-seven when he set sail for Mexico with Chandler and Tina Modotti by his side. This was a journey of separation that was both real and psychological. Indeed, it is easy to imagine that if Weston had not made this break, his future as a photographer and as a person would have been severely crippled, if not extinguished. Today, he might be no more than a footnote among the many forgotten personalities from the romantic heyday of Pictorialism.

His letters and diary entries provide an important insight into the struggle that consumed him. Writing shortly after his arrival in Mexico, he addressed a letter to his youngest son, four-year-old Cole: “You rascal – you rogue with laughing eyes! You are right in my arms now – or on my shoulders – while I go prancing around the room like mad – right here I tell you! – and then I get a queer feeling when I awaken and wonder if the next time I see you – you’ll be too big a boy to ride on daddy’s shoulders -“. In closing, he provided a peace offering to Flora and a bit of fatherly advice offering, “Kiss your mother for me – and be good to her – keep your nose clean and your pants dry – and listen to the little pine trees whisper in the evening breeze – they’ll tell you a secret – “I love you” – Daddy.” One can only imagine the tugging on his heart when he received letters “of most importance” that came from his sons, “illegible scrawls” that he described as containing the constant refrain “Dear Daddy, when are you coming home?”

Edward’s devotion to his sons made his separation from them very painful. In writing to them from Mexico City, he told them that he had taken the “little thumb-worn” copy A Child’s Garden of Verses (how many of us can remember with great fondness that important book from our toddler years?) and pasted their pictures in it. “It is on my table where I write and I turn to it in lonesome moments – when twilight comes or with my morning coffee – it gives me pain and pleasure mixed – write me – tell me what you do – how big you are and many little things that I should like to know.” One can share his angst despite the passage of time. In an equally emotionally charged letter, he wrote, “I send you kisses – kisses – kisses . . . The other day when I sat here resting and dreaming – I thought of that night we walked to the river together – into the dark night. I could still feel your little confiding hand in mine – and see your furtive upward glances as though to be reassured that there was nothing to fear.”

Weston sought solace in his works and his growing circle of friends. A telling moment is revealed in his Daybooks when a burst of anxiety is poured onto the page expressing his deep desire to be with his other sons: “I danced many times and furiously, – it was distraction I needed. I am most assuredly not mentally calm. The ghosts of my children haunt, their voices, their very accents ring in my ears. Coles’ merry laugh, Neil’s wistful smile, and blue-eyed Brett’s generous gestures.” You can feel his near desperate longing when he concluded this thought: “Some solution must come; I need them, they need me.” Weston’s dreams and daydreams were filled with images of his boys’ smiles. His letters home are filled with passages retelling his previous night slumber stories: “I held you on my lap – I kissed your broad fair forehead – and you cuddled close – patted my cheek and asked for stories – your hand crept into mine . . . dear dreamer on the lap of one whose dreams allude – you with tender tears in the arms of one whose tears are almost spent.” In this same latter, he opened a window to the very deepest part of his soul when he offered his protective services as a father from afar:

As I looked down upon you – you became . . . the symbol for all in life of tender hopefulness born to the easy prey of those who gibe and jeer – they will flout you – insult you – lynch you – but I will protect you for I have masks that you shall wear – a horned and grinning devil – a sharp beaked bird – a ram in solemn mummery – I have them – I shall keep them for that hour when it must be you shall need them – to hide behind and keep inviolate . . . within which is yourself – they shall be my only legacy to you.

Dreaming provided an outlet for his anguish and loneliness. In a letter from the glistening harbor in San Francisco, where “everything is clear and sparkling . . . a wonderfully beautiful sight,” he wrote Cole that this is a “place to dream.” He lamented, “If one had time or inclination to day-dream – but this world has no place for dreamers though it is glad enough to use the things that come from dreams providing they cost nothing! – and sometimes the world is very much afraid of dreams if the dream be more than about corn-beans or cabbage boiled.” Whether Cole’s mother read him this missive will never be known. But it is clear the message was as much for Flora as it was instruction to his son, especially when he goes on to say, “If one were to pour claret on strawberries instead of cream and sugar or put a dash of cognac in his coffee in place of ‘canned cow’ something terrible might happen to the poor fool who dared to try such outlandish experiments.”

To Brett, he offered fatherly advice for a boy who was quickly maturing and, in his eyes, destined to be a “heartbreaker with the ladies.” He advised, “but watch out for them . . . You’ll be the butterfly, and maybe break your wings. You can’t fly to foreign lands after gold and lost Gods. But if you don’t get trapped, you may in your search for gold and conquest, land on some cannibal island to become the Fair White God of a swarthy race. Wear a plumed hat and a jeweled sword, ride an elephant and have a hundred coal black wives to wash your socks and tickle your toes!” These are words of encouragement on adventure, the perfect language for a thirteen-year-old boy yearning to venture from the confined of life in Glendale while his father and older brother are in Mexico.

In writing to Cole in 1924, his “baby” at only five years old, he exclaimed, “My greatest desire is for a ten minute romp at hide-and-seek with you, to hear your shrieks of joy, to see your eyes snap and sparkle, or to have you jump from terrific heights of some table – jump with a shiver across the yawning chasm below into the sure safety of my arms.” These were words of assurance for his young son and, without a doubt, served as a source of solace for Edward’s own well being.

It would be easy to overanalyze these passages and overstate their meaning. Suffice it to say that two important messages are clear: First, that he had a deep commitment and love for his sons; second, that he could not shake his inner torments. This anguish caused Weston to leave Mexico in 1924, only to return nine months later when he found the hardships of home life with Flora to be more unbearable than the separation from his children. Clearly, despite advances in his art, Weston’s personal life remained in shambles throughout his journeys to Mexico. It was at this stage in his life that his relationship with his sons was at its most vulnerable point. They were young and highly impressionable; they were not mature enough to understand the reasons for their separation from the father they loved so dearly; and they were under the stern and direct influence of their mother, who was suffering her own version of personal torment. Edward struggled to remain a positive presence in their lives, which must have seemed insurmountable for him.

Returning home to California, Weston’s focus on his sons never waned. In 1927, he noted that “Saturday is the boys’ day – the lithe fellows, Neil and Cole. I close up ‘shop’ and we wander away wherever their fancy lures, to the zoo, rowing, or to the museum.” On another occasion, Weston recorded an outing with them: “Perhaps the most fun I have had lately has been in a swimming hole discovered by Cole and Neil. It was reminiscent of Huckleberry Finn, with bonfires, rafts, and naked boys. Fed by fresh river water this hole gouged out by steam shovel is deep enough for diving, and much larger than the local swimming tanks. It is hidden from public gaze so no spinster can be horrified by naked boys and men.” His love for his sons was reciprocated with equal fervor. Writing to his father what Edward described as a beautiful letter, Brett exclaimed, “I care for you more than anyone else.” Of Brett, Edward reflected, “We are much alike in many ways, yet so different in others. Maybe the differences are only in the matter of years . . . Our mutual love, compatibility, would have held us together, – and maybe – no, I’m sure, – to his detriment.” His adoration of his sons extended to the next generation of Weston’s as well. On the birth of his first grandchild in 1930 (coincidentally on Edward’s birthday), he wrote a letter to the proud parents, Chandler and Maxine, “Dearest Children – Max and Ted – I feel so emotional, and am so excited I can hardly write! Bless all three of you!” On his grandson’s first birthday, he wrote, “Teddy darling – Today is our birthday, our first together, though we are physically a few miles apart . . . and I send you many kisses and hugs and so much love – Grandpa!”

Edward had a special relationship with each of his sons. His ties to Cole as “baby” were different from those to his other sons, possibly because Cole was the youngest. When Cole was only eleven years old, Edward reflected, “Cole, – the baby, yet I would guess the oldest soul of them all: a little rogue, but a dear rogue, with mischievous ways and dancing eyes, – yet he does at time evoke in me much sadness: I have seen his face in repose filled with indescribable pathos, as though he’d known, knew, or would know a world’s affliction.” Cole had been only four years old when his father departed for Mexico in 1923. Cole’s early life revolved around his mother for many of those formative years. Even after Edward returned from Mexico the second time in 1926, he continued his wanderings for much of the remainder of Cole’s childhood. In 1934, when fifteen, Cole begged his mother to allow him to live with his father in Carmel. His parents consented, and shortly thereafter, Weston moved to Santa Monica, California, where brothers Neil and Brett joined Cole in yet another gathering of father and sons under one roof. It was an arrangement that repeated itself in different combinations for much of the remainder of Edward’s final two decades. Cole eventually returned to assist his father in the darkroom after World War II as they continued to enjoy a strong and inseparable bond.

One interesting aspect of Weston as a father is his philosophical wanderings on the subject. Weston imparted a great deal of advice to his boys when they were very young. It was his hope that near or far, he could help mold them into the men they should become. Reflecting on Brett, who was “overflowing with life” and full of love for adventure and experience, Weston knew that he was “open-faced, laughter-loving, amenable to suggestion.” Edward concluded, “I hope to help him when he stumbles or give him a gentle kick in the right direction – if I am able to decide which is right, at the time!” To Brett, he wrote and stressed the importance of “being himself”: “Always be Brett Weston – be yourself! – it is by far the hardest way to live to be true to oneself – regardless of opinion – it is like rowing a boat upstream – a continual struggle – but only in this way can you live out your destiny.” A more concise and distinct statement of Weston’s life philosophy would be hard to find. The phrase is echoed in a passage he wrote into his diary admonishing others, especially Flora, no doubt, that, “I must think of Edward Weston first.” He believed an individualistic attitude toward life was not selfish; rather, “in fact it is most natural, a law of nature touching everyone, everything.” He struggled between the two spectral ends of self-interest, especially as it pertained to his work, and selflessness – his “emotional, personal” love for his children. It was a struggle that he continued to face for much of his life.

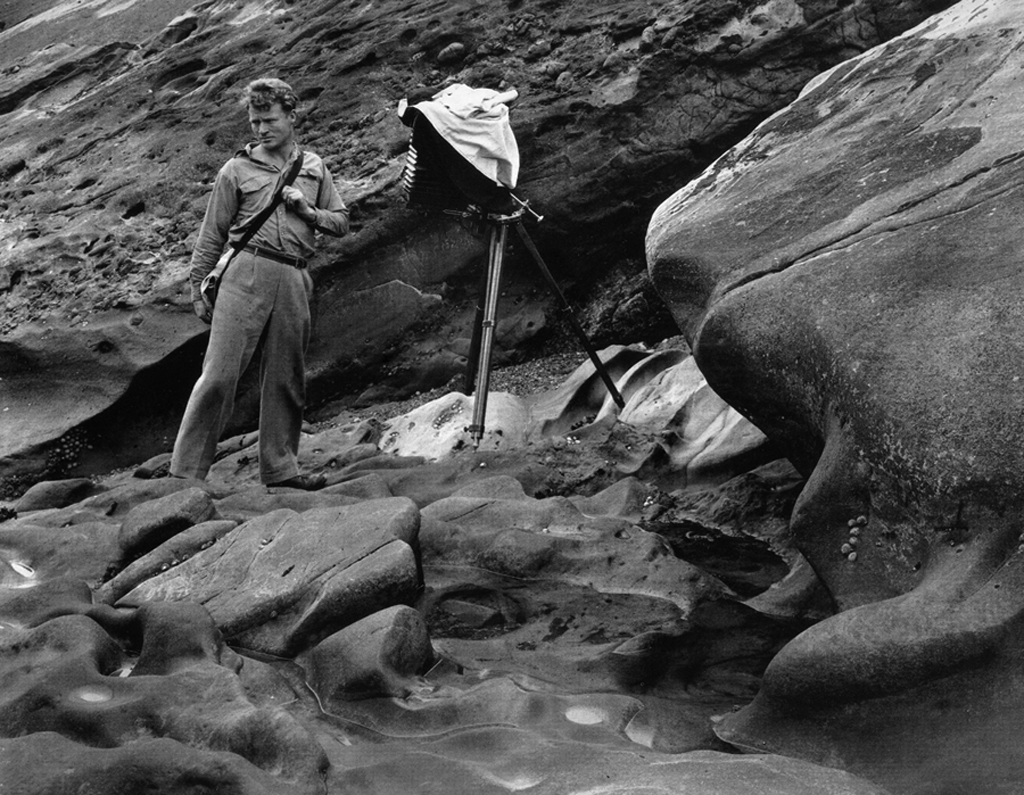

Quite possibly, Weston’s fondest moments as a father were those coupled with his life in photography. Each of his sons adopted Weston’s love for art. Brett and Cole went on to distinguished careers as photographers of importance in their own right (the family tradition continues with his grandsons including Kim and Matt). One particularly touching entry in his daybooks came from an encounter with fifteen-year-old Brett while on a journey to San Francisco. He wrote, “I wish Brett knew how my heart was warmed by a request of his last night. ‘Dad.’ ‘Yes.’ And then he hesitantly as though asking a great deal, ‘I should like to have a couple of your photographs for my own.'” Edward repaid this compliment many times, commenting, “I wish I had taken that.” The spiritual connection between father and son, photographer and photographer, ran deep. At Point Lobos in 1930, he paid Brett the ultimate praise: “Not till I focused did I realize, recognize, that I was using one of Brett’s details, an insignificant bit – at first glance – which he had glorified, used in one of his best-seen negatives. Brett and I were always seeing the same things to do – we have the same kind of vision.”

In 1945, when joining his father after his hitch in the Navy at the close of the war, Cole wrote him,

You will never know what those six days with you meant to me, photographically and otherwise. Your calm, collected and simple approach to the complexities of life will always be something for me to remember and think about. I’ve always felt that if in my lifetime I can become half the person, make half as much out of it as you have, I will be satisfied, after your wonderful visit I feel this even more strongly.

He signed that letter with “Much love, Your ‘hope to be a good photographer son,’ Cole.”

His philosophy of father hood was not something he willingly shared. In response to queries from his sons on providing pointers for the ‘prospective father,’ he told Cole and daughter-in-law Dorothy that he would decline their invitation to dispense parental advice. Although he was flattered, he wisely asserted, “I have a feeling that you two will have the answers when the time comes. You know how I feel about well-meaning meddlers, those who would prevent us from the great experiences of making mistakes. However, we will have a good exchange of ideas upon the flat one fine day.” A letter to all of his sons spelled out this perspective in much greater detail. The letter also served as a sort of confessional for himself and a means of possible absolution for his boys.

There is so much that I have wanted to write “you-all.” It can no longer be father to son stuff, but man to man. As a parent I have painful memories of my failings – I guess every parent must have like pangs. I can only hope that my sins have been those of omission rather than commission. I have seen too many parents living their children’s lives for them, actually preventing them from making mistakes and so stunting growth. Of course, these parents love their children, but with a Shylock’s love, expecting, demanding return. I am making excuses for myself, of course; for I have gone the other extreme in wanting you to have your own experiences, live and learn from them. Maybe not in wanting to preach, I have not talked enough. Question, question, question – always two sides and which is the right answer.

Echoing this perspective, Weston was true to form in practice. His daughter-in-law and protégé Dody Weston Thompson, later reminisced that Edward was not only one of the “nicest human beings I ever knew,’ but that he was “unfailingly kind” and most of all, “undemanding in his affection.”

His yearnings for his sons continued to be expressed in his correspondence. Writing to his sister, Mary, he thanked her for birthday wishes but lamented that “my wants were far away in Glendale, Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Connecticut.” This is echoed in a 1945 letter to his sons: “Blessings bear children for calling your Pops. The sound of your voices was sweeter than music.” In response to a letter from Neil, he replied, “Your letter (8 pages, count ’em) was about the best Xmas present I could have had.”

Clearly, when he wrote to Neil that next year, he expressed his innermost feelings by exclaiming, “I say that my 4 boys are the finest ever born, best looking, smartest, sweetest.” His positive mark on each of them was indelible. Even Flora remarked, “You have made “Men” out of them.”

Nyerges, Alexander Lee. “Edward Weston: Lover of Life.” Edward Weston

A Photographer’s Love of Life. Dayton, Ohio: The Dayton Art Institute, 2004. 21-93. Print.