Edward Weston was a complex man. Often portrayed as a philanderer, a consummate Don Juan with a camera, he was much deeper and caring: a respectful son, a caring brother, a loving husband. A doting, proud, and engaging father, the real Edward Weston was a man whose philosophy of life, art, and love were inseparable. His world, often overly egocentric, was one built in passion, enthusiasm, and love.

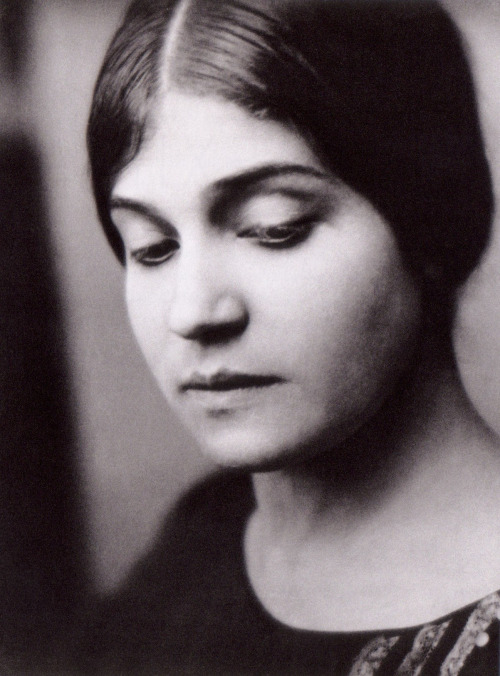

One needs only to read the words of Tina Modotti to understand how Weston gained such notoriety as a lover and a womanizer.

One night after – all day I have been intoxicated with the memory of last night and overwhelmed with the beauty and madness of it – I need but to close my eyes and find myself not once more but still near you in that beloved darkness – with the flavor of wine yet on my lips and the impression of your mouth on mine. Oh how wonderful to recall every moment of our frail and precious dreams – and now while I write you – from my still quivering sense rises an ardent desire again to kiss your eyes and mouth – my lips burn and my whole being quivers from the intensity of my desire . . .

It was more than his personal charm that attracted women. His ability to write, something he often considered a shortcoming, was magical as well. Consider this response from Tina Modotti to a letter he had written,

Once more I have been reading your letter and as at every other time my eyes are full of tears – I have never realized before that a letter – a mere sheet of paper could be such a spiritual thing – could emanate so much feeling – you gave a soul to it! If I could be with you now at this hour I love so much, I would try to tell you how much beauty has been added to my life lately! When may I come over? I am waiting for your call.

Weston had an almost mystical attraction for women. It was this quality and his tale-telling abilities, especially in his Daybooks, that has given rise to the impression of Weston as the consummate ladies’ man. Perhaps it is passages such as his brief aside from April 20, 1927, when he noted, “my life may become complicated with three lady loves to consider.” Weston recorded his love life in considerable detail for readers of his diary. This provides only a momentary glance into his psyche and therefore distorts the much larger and more complex picture for the reader. An illustration of this is the often-quoted passage from 1923 when Weston recorded doubts about his relationship with Tina Modotti and his love affairs in general. He wrote, “Bare-foot, kimono-clad, Tina ran to me through the rain – but something has gone from us. Curiosity, the excitement of conquest and adventure is missing. ‘Must desire forever defeat its end?'” At first glance, the implications and conclusions one could reach include the picture of Weston as a shallow and soulless man. Nothing could be further from the truth. These are the self-doubts that Weston later ascribed to his wish to “let off steam,” a result that he admitted “gives a one-sided picture which I do not like.” Chagrined, Weston shrugged saying, “I rebel too, reading my opinions of a few years ago, but these I can at least pass with a shrug and smile, as I will this writing two years hence – ” Despite knowing that he would disagree with his diary in the future, Weston continued to write his thoughts and feelings in almost an insatiable manner. And we are quite thankful for his momentary insights no matter how skewed they later appear.

Tina Modotti shared Weston’s penchant for writing as well as the need to record on paper life’s “little black moments.” She wrote him, lamenting, “A few days ago I wrote you again but now I almost regret having sent it; I was in such a despondent state of mind and weak enough to not just keep it to myself and made you the victim of my weakness.” Quite possibly, Weston wholeheartedly agreed with Tina not only for her regrets, but also for his moments of weakness with the pen (or pencil as was the case for Edward Weston). Earlier, Weston had recorded his own lament about his lack of confidence in his writing abilities. “I seem to read between my lines something quite different from what I wrote, yet I try to be genuine, and imagine myself so at the moment. But when I glance back over myself speaking on such and such a day, I either snicker with amusement, or get a belly-ache, or ‘see red.'”

“I have no illusions about the women who fall in love with me. I am in the same boat with the man of wealth. He attracts with gold, I with the glamour which surrounds me, much as the torero or champion pugilist or matinee idol fascinates. Women are hero worshippers. I suppose it has a biological reason, and unconscious selection of the finest type – according to their light – as a feather. I would like to be loved for myself: which means I would like to be a highly charged sexual animal. But would I? We can’t have everything! I am a poor lover, in that I have no time or desire for sustained interest. I make a grand beginning, then lose out through indifference. The idea means more to me than the actuality.”

In response to this passage, Charis Wilson later remarked, “Particularly disconcerting were the diatribes [from his Daybooks] on women . . . I could not imagine him talking or behaving that way in person. The voice in the Daybooks was dogmatic, didactic, and judgmental, whereas Edward himself was open-minded, un-presumptuous, even diffident.”

Weston’s description of love changed as he matured. In an undated Daybook entry that is likely from before 1923, a young Edward Weston recorded his thoughts about photography and reminisced about his youth in Chicago, “. . . denying myself every luxury – indeed many comforts too – until with eleven dollars in my pocket I rushed to town – purchasing a second-hand 5 x 7 camera – with a ground-glass and tripod! And then what joy! I needed no friends now – I was always alone with my love.” Although the words clearly express the thoughts of a man who would place the love of an inanimate object, a machine, above all else in this world, we know this is not the case. We read the words of a less mature man, one who is searching for both purpose and meaning in his life.

While on his first journey to Mexico, Weston, along with his eldest son Chandler, his mistress and photography partner Tina Modotti, and his friend Mexican Senator Manuel Hernandez Gavlan, were hiking through the rugged wilderness near Mazatlan, climbing through purple lupine taller than their heads, fighting a gale-force wind that swept through the pines. “We climbed up and up, stumbling forward, slipping back. I was the rear guard. My camera slowed me down. It was always so. I pay the price of my lover, – perhaps my only love.” Clearly, his state of mind was not the most positive. With him on that trek in Mexico were three people, all very important to his world. Despite the fact that nothing was more important to Weston than his affection for his sons and their affection for him, he nonetheless concluded that his camera was his only love.

Even as late as 1928, Weston reflected in his writings, “What is love! Can it not last a lifetime? Will it never be for me? Do I only fool myself, thinking I am in love, and really never have been?” The next month, Weston lamented at the end of a relationship to a woman he records only as “A.” and continued the doubts that racked his consciousness, “It surely was not really love I felt for her, I was in love with the idea. But what is love? What has happened to the many girls I have thought I loved? Is love like art – something always ahead, never quite attained? Will I ever have a permanent lover? Do I want one? Unanswerable questions for me!” The uncertainty is normal. Our fragile existence often leads us to momentary pauses and doubts, some more pronounced and real than others. Relationships by their very nature are frail at best and subject to considerable external as well as internal forces that make them unstable, even under the best of circumstances.

It is not until he met Charis Wilson that Weston found the comfortable, sharing relationship he had been seeking. In Charis there was a healthy does of maturity and security. Shortly before meeting her, Weston had very carefully underlined a passage in the Keyserling book The World in the Making: “To love is just as natural to man as to take; the instinct to give himself is as normal as the acquisitive instinct.” Charis observed later that Edward was “drawn to the inspiration that falling in love provided – the deep connection and communication with a new person. The best evidence that most of his relationships with women were not mere dalliances was their endurance. He maintained friendships with many of his former lovers until the end of his life.” This was also true of his relationship with Charis, which ended in divorce in 1946; the longest and clearly most satisfyingly meaningful relationship with a woman Weston enjoyed.

“To live for others is one true way of living for oneself, for the spirit is essentially outpouring.

”

Weston’s attraction to women was far more than sexual. His own words are most telling: “All these women – what do they mean in my life – and I in theirs? More than physical relief – one woman would be sufficient for that . . . Actually it means an exchange, giving and taking, growth from contact with an opposite . . .” In his journal he mused, “I was meant to fill a need in many a women’s life, as in turn each one stimulates me, fertilizes my work. And I love them all in turn, at least it’s more than lust I feel.” Weston’s capacity to love and then move on was paralleled in his work. Reflecting on the success of his first book in 1932, “This book, like an exhibit, marks the end of a period. I turn the pages, each plate an old friend, each recalling red-letter days, – and know that I must go on from these, leave them as I leave my love affairs, still loving them, but with no regrets.”

Perhaps the attraction was what Nancy Newhall called “the real Edward Weston quality . . . gaiety, toughness and affection.” Whatever the reason, Weston clearly possessed an uncanny ability to establish and maintain relationships that had both depth and longevity as hallmarks. Charis Wilson later recollected, “He was certainly a romantic at heart. I think it was a dated romanticism that he brought from a previous century. When he starts writing one of those purple passages in his Daybooks, it is very clear that he consciously is making this stuff work this way and this is how he sees it.” Lover, romantic, by any description, the heart of Edward Weston was large and forever giving.

Nyerges, Alexander Lee. “Edward Weston: Lover of Life.” Edward Weston

A Photographer’s Love of Life. Dayton, Ohio: The Dayton Art Institute, 2004. 21-93. Print.