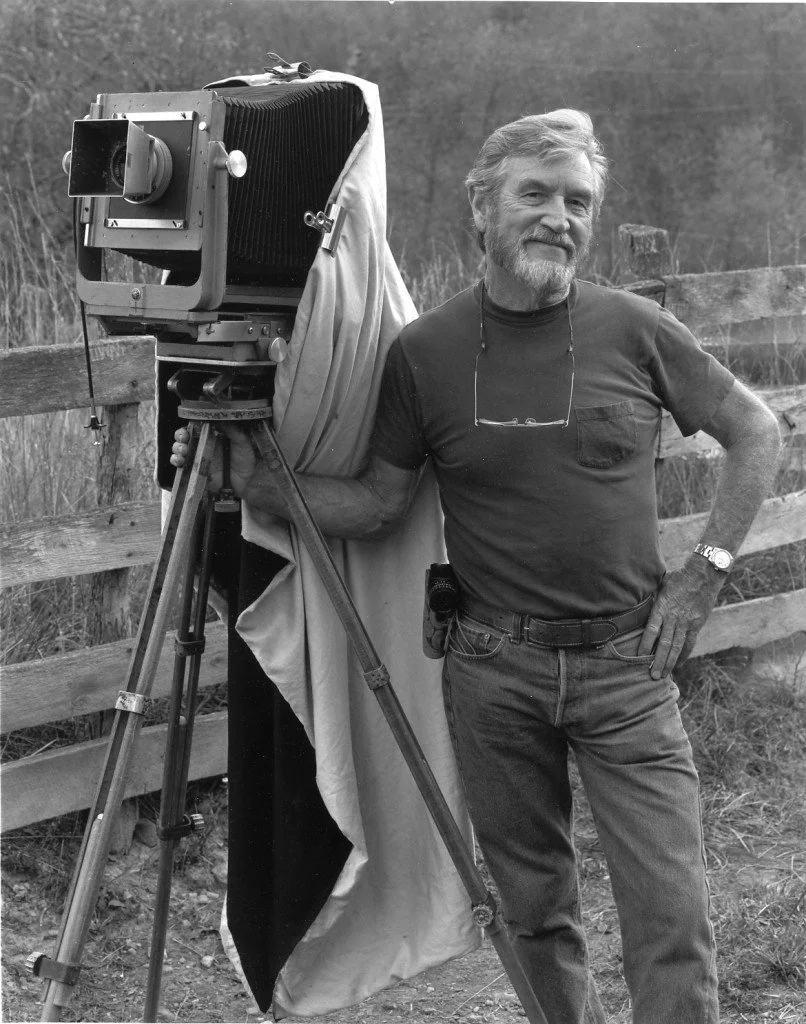

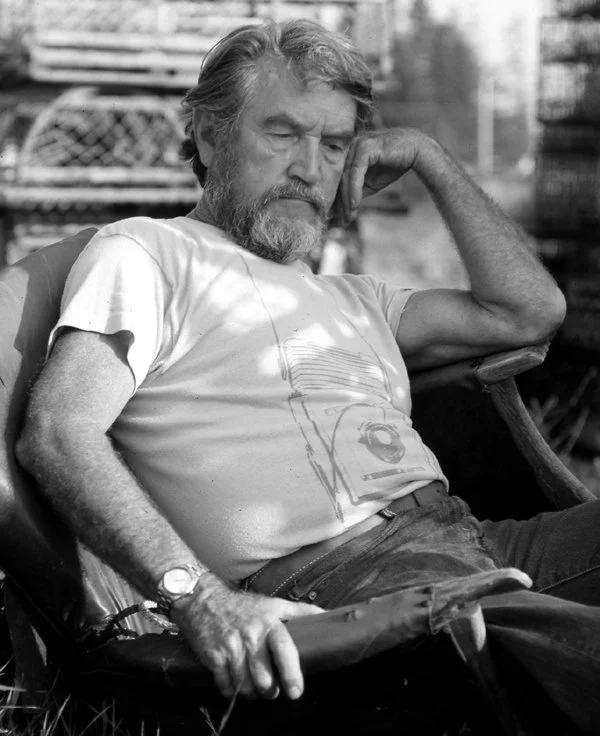

Happy Birthday, Cole Weston!

Cole Weston would have been 98 today. We continue to be inspired by his passion and dedication to his and his father's art.

"At the beginning of 1945, the eminent photographer Edward Weston wrote a birthday letter to his 26-year-old son, Cole, serving in the US Navy:

My mind is teeming with your new adventure, photography. Naturally, it is a tremendous subject for me, has been for 43 years. So I am stymied when I try to say anything, give you advice in a mere letter. So for heaven's sake get a leave and we will sit, or lie, up on the flat and talk it out.

There are two approaches, maybe three, to any art: you can make it a real business first of all, in which case "Art" could, probably would, be killed; or you can live for your art, and maybe grow lean in the living, or try to combine the two approaches. In trying to achieve the latter, I have learned that you can't make a lot of money, get rich, out of your own hide, no less than the corner grocer; that if you wish to go alone and live an unharried life, eat well enough and support wife, mistresses or children (or all six at the same time) then you must give the public something they can't get elsewhere.

When Cole Weston received this advice, he had already been trained in the Navy as a photographer. At the end of the Second World War, he worked briefly for Life magazine in Los Angeles, but the quick-fire story-based practice of reportage was alien to the meditative, carefully composed photography which he had learnt from his father: "I had been trained to make one or two exposures of a subject. Either you had your image or you didn't."

Like his father and his brother Brett, who also became a distinguished photographer, Cole was fascinated by the spirit of things – objects, places, the human form – and by the ways in which photography could transcend the everyday, and produce monumental and mystical images. The Westons were immersed in the natural world, the awe-inspiring landscapes of northern California, the structure of plants and the shifting plains of the ocean. As America engaged in its ongoing love-affair with consumerism, the Westons, while appreciating modernist forms, celebrated its natural heritage.

Although Cole Weston was determined to make his own way as a photographer, his future was to be intimately connected with his father's career. Edward Weston was already hailed as one of America's most significant photographic artists, and his close friendships with photographers such as Ansel Adams and Tina Modotti made him part of an élite grouping which would dominate US thinking on photography for decades.

In 1946, a major exhibition of Edward Weston's work opened at the Museum of Modern Art (Moma) in New York, where the photography department was rapidly establishing itself as the key player in the post-war photography scene. His powerful images and masterful black-and-white printing were the ideal antidote to the reportage which had dominated the American imagination during the Second World War. But he had developed Parkinson's disease, and Cole abandoned his Life assignments to become his father's assistant and printer, even taking photographs under Edward's direction: "He would tell me where to set up the camera and he got so bad I would literally put his hands on the focusing knob."

Edward Weston had four sons. Two of them, Cole and his older brother Brett, became part of the Weston legend, working with their father and producing their own work. Though both were successful – Brett in particular was frequently published and shown – their careers were dominated (and powered) by their father's reputation and output.

Cole Weston worked as Edward's assistant at his Carmel studio from 1946 until Edward's death in 1958. In his will, Edward had specified that only Cole was authorised to print his negatives. Though prints produced by Edward himself were valuable and much in demand by collectors, there was also a substantial and continuing demand for Cole's prints from his father's negatives. The photographic dynasty created by Edward, Brett and Cole fascinated the photographic community and, together with his son Kim, Cole continued to organise and lead masterclasses in photography into his eighties.

Although Cole Weston was born into the tradition of craftsman- produced black-and-white art photography, he was to find his own photographic direction in colour. The Eastman Kodak company provided Edward Weston with colour film at the end of the Forties, hoping that his endorsement would establish this new technology beyond the commercial sphere. Though Edward remained wedded to black-and-white film, Cole was intrigued by the possibilities of colour, and began to photograph the land- and seascapes on the remote and beautiful pacific coastline around Carmel. In 1988, Aperture published At Home and Abroad, a retrospective collection of Cole Weston's colour photographs, in which his fascination with the landscape and the female body was explored in a series of sensuous and richly toned images.

As close as Cole was to the Weston photographic legend, he was determined not to be overwhelmed by it. In the late Thirties he had studied theatre arts at the Cornish School in Seattle and in Carmel became active in the Forest Theatre Guild, directing productions which included Of Mice and Men and Camelot.

As a gallery artist, Cole exhibited frequently, and his work was collected by institutions which included Moma in New York, the Philadelphia Museum and George Eastman House, Rochester. He was included in the exhibition "The Photographer as Printmaker" shown in London and throughout the UK in the early 1980s.

Cole Weston, like his father, epitomised the ruggedly masculine persona which would become iconic in US photographic mythology. Interviewed recently, he remarked that "the four important things in my life have been photography first, theatre, sailing and then women and wives". To that might be added his devotion to, and perhaps obsession with, a father whose achievements were always destined to overshadow those of his two photographer sons."