"Connection is the Point": Kim Weston on Art, Vulnerability, and Breaking Free from Legacy by Thomas Berlin

There's a particular kind of courage required to step out from the shadow of a famous grandfather—especially when that grandfather is Edward Weston, one of America's most celebrated photographers. But in a recent conversation with photographer Thomas Berlin, Kim Weston reveals something unexpected: his artistic journey wasn't about escaping legacy at all. It was about following an inner compass toward something more complex, more collaborative, and deeply personal.

From Darkroom Child to Studio Artist

Kim's earliest memories are of perching on a stool in his father's darkroom, too small to reach the sink. "I was a very shy kid," he recalls. "It was just me and my dad in there, and it was dark." What began as childhood enchantment eventually evolved into something more deliberate. While he started photographing in the classic Weston tradition—rocks, trees, landscapes alongside his father Cole and uncle Brett—something was missing.

"I wanted more control over filling the rectangular frame," Kim explains. "With landscape photography, your control is limited to composition, lighting, and timing." So he moved into the studio, where he could build and paint sets, choreograph scenes, and most importantly, work with models. For over thirty years, this became his domain—a place where he could work through whatever was happening in his life, whether emotional struggles or personal challenges.

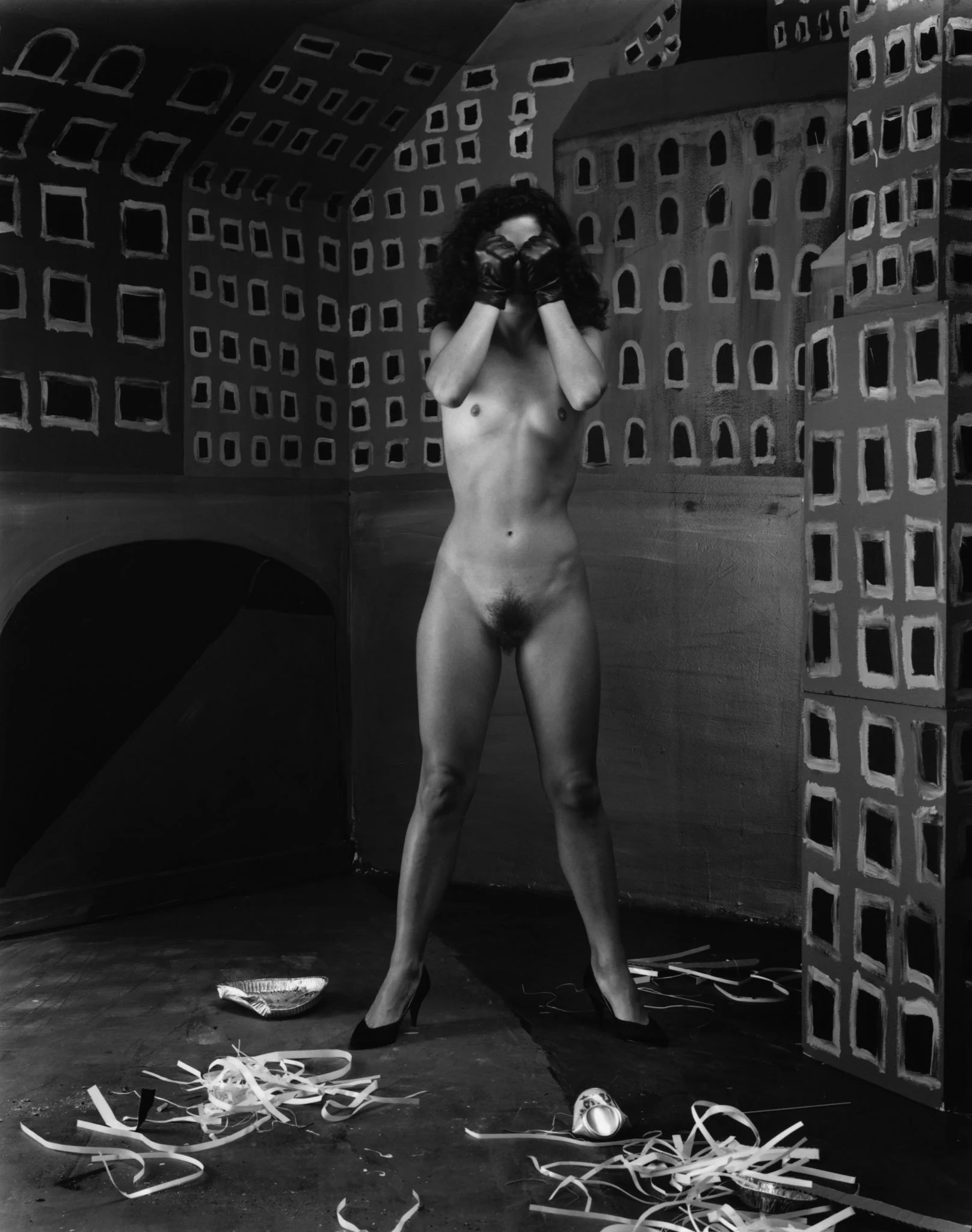

Kim Weston’s Self Portrait #13, c. 1993

Kim Weston’s Head down nude with Cow, c. 1993

The New York Story: Art as Emotional Processing

One particular story stands out, revealing how deeply personal Kim's work has always been. Years ago, he traveled to New York for the first time. Having grown up in the country and attended a one-room schoolhouse, the city overwhelmed him. "The crowds, the noise, the indifference of people—it was shocking," he remembers. He had planned to photograph outdoors but ended up staying in a friend's studio instead.

When he returned home, Kim did something remarkable: he built his own miniature version of New York in his studio—tiny buildings, streets, crowds—and placed a model inside. "She became a stand-in for me, representing my own vulnerability and fear of the city," he explains. This kind of projection would become central to his work, transforming the studio into a space where inner landscapes could be externalized and explored.

Kim Weston’s New York City, c. 1986

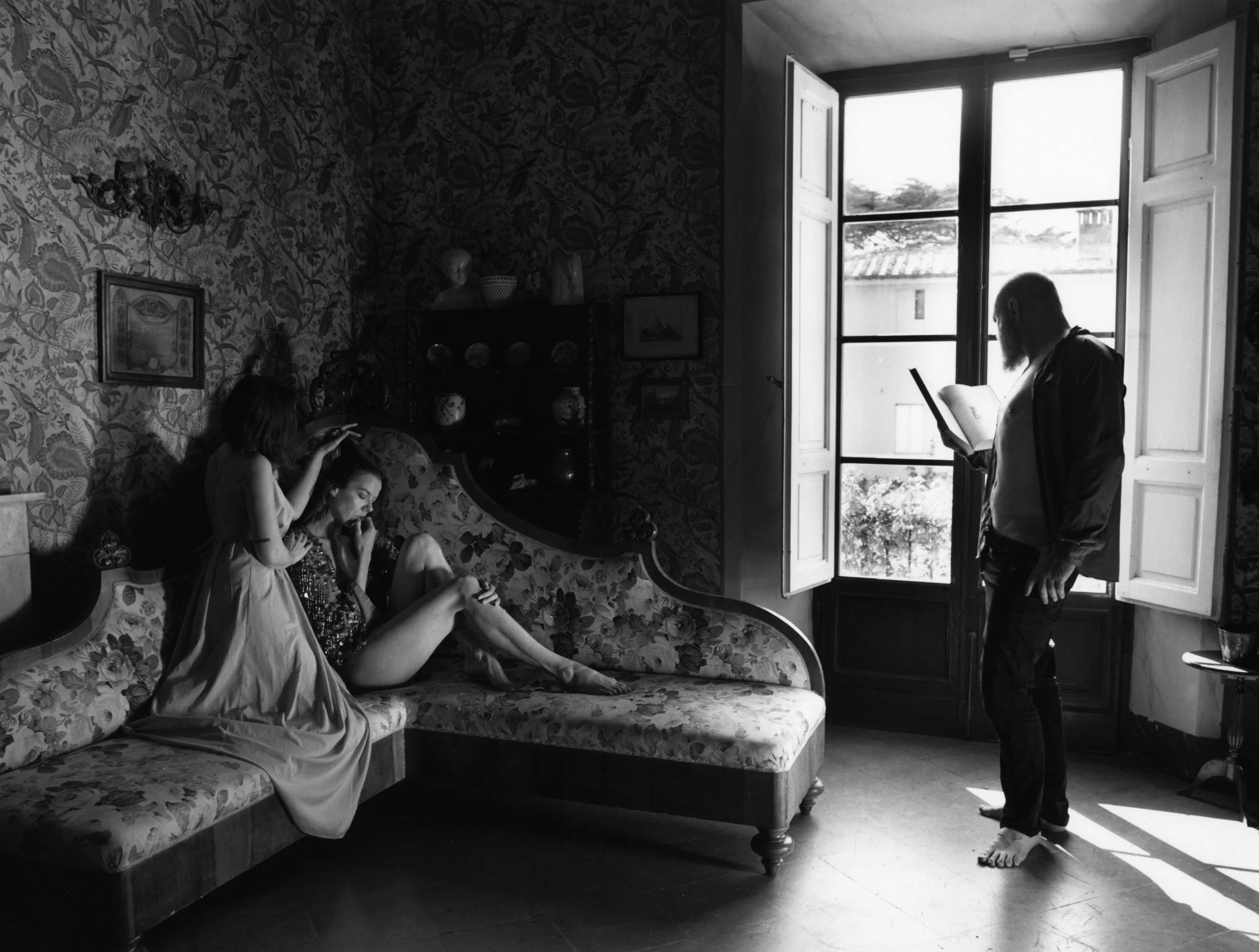

The Art of Collaboration

What sets Kim apart from his family's tradition of straight photography is his emphasis on human connection. "I love human interaction," he says simply. "Working with another person is a much more complex challenge." Early on, he photographed friends and girlfriends. Then came Gina, who modeled for him for twelve years before telling him she was done. The announcement forced him to work with professional models for the first time—and transformed his entire approach.

"With professional models, it became a dialogue," Kim explains. "Sometimes they would direct me." He compares the process to theater, with the model as actor and artist as director—except the roles blur and merge. "A great model is an artist in her own right, using her body as a brush." They look through art books together, studying painters like Degas and Balthus, and create something inspired by those references. The photograph captures not just the model but the energy between them, everything that led up to that decisive moment.

Embracing Failure Through Paint

After fifty years of mastering photography, Kim deliberately sought uncertainty. He began adding oil paints and pastel chalks to his black-and-white prints, creating hybrid works that blur the line between photography and painting. "I wanted something new—something I could fail at," he admits. "That sense of uncertainty felt essential, almost like returning to the excitement of being a child making the first photograph."

He set himself strict rules: fifteen minutes per piece, no going back. "I wanted to throw myself into it and attack it," he says. The time constraint prevents the work from becoming precious or overworked. When it's done, it's done. This willingness to risk failure, to embrace discomfort, reflects his larger philosophy about art: it's a way to learn about yourself.

The Power of Presence

Throughout the interview, Kim returns again and again to the concept of connection. When teaching workshops, he insists everyone start with a tripod—not for technical reasons, but to force them to slow down and think before pressing the shutter. He tells students that the model isn't just a subject; she's another human being. "You need to connect. Talk. Collaborate. Otherwise, you're just taking pictures, not making them."

He even made a series of nude self-portraits—"just for myself"—to understand what it feels like to be on the other side of the lens. "I wanted to experience what it feels like to be seen, to be exposed. It completely changed the way I work with models."

Art for Oneself, Not the Market

Perhaps most refreshingly, Kim is unapologetic about creating for himself first. When asked about his audience, he's direct: "Audience comes last." He recalls a friend who often says after making a photograph, "They're going to love this." Kim has never said that. "I've never cared whether someone else would love my work. For me, photography is self-centered in the best way."

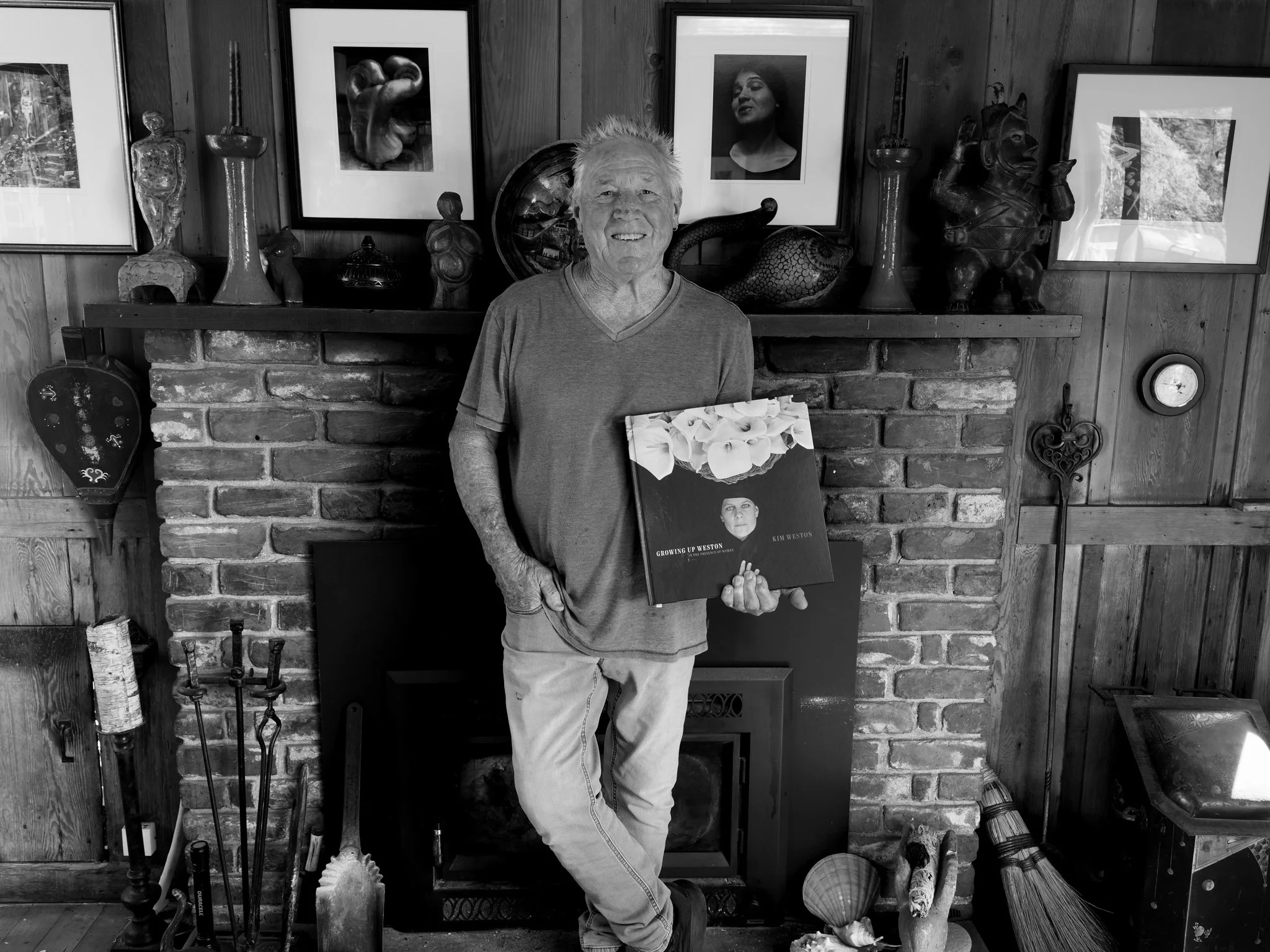

A Book Six Years in the Making

Kim's recent book, Growing Up Weston, represents a lifetime of work—literally. It took six years to complete, with significant help from Gina and friends. For ten years, from 1979 to 1989, he mounted each negative on the back of its print as a reminder that no single image was sacred. "It wasn't about one great image, but about growth as an artist," he explains.

The book is deeply personal, featuring contributions from the models who collaborated with him—they wrote their own sections. Some people told him he revealed too much. His response? "I've never felt the need to hide. I just wanted the book to reflect everything—from my earliest work to now." That includes the painted photographs, which came later in his journey. If he'd published earlier, that evolution would have been missing.

Living the Legacy at Wildcat Hill

Today, Kim lives with Gina at Wildcat Hill in Carmel Highlands—the same house where he met his grandfather Edward at age five. "I'm sitting at the same table where I first met him," he reflects. The house isn't a museum frozen in time but a living space where art continues to evolve. Gina manages the business side while Kim focuses on teaching and creating.

Their son is now a photographer too, following in the family tradition but finding his own voice. "Seeing that continuation means everything to me," Kim says. And in that statement lies the real legacy: not a specific style or technique, but the courage to be honest, vulnerable, and fully present in one's art.

As Kim puts it simply: "Connection is the point."

Kim Weston at Wildcat Hill. Get your copy of Growing Up Weston today!

A heartfelt thank you to photographer Thomas Berlin for this extraordinary conversation. His thoughtful questions drew out insights that go far beyond technique—they reveal what’s underneath the artist.

The full interview delves even deeper into Kim's philosophy on art, his thoughts on the analog versus digital debate, the role of galleries in contemporary photography, and intimate stories about life at Wildcat Hill. If these excerpts resonated with you, read the complete interview on Thomas Berlin's website—it's a master class in what it means to be an artist.

Learn more about Kim Weston's work, workshops, and his book Growing Up Weston at kimweston.com.